Never Hurry a Bear—Or, a Book

UPDATE ON MY MEMOIR ‘BLACK BEAR’ AND OTHER BEAR STORIES

I made several mistakes on that cool, damp, low hazard day at the fire tower in July 2022.

I’d only intended to go for a short run to stretch out my legs before ‘sked’, what lookouts call the mandatory radio check-in that occurs everyday, on the minute, at 1900. I always said jokingly (though knowing it was true) that the whole point of ‘sked’ is for dispatch to ensure: Are you still alive out there?

My first mistake was that I didn’t bring a hand-held radio. My second mistake was that I’d intended for it to be such a brief foray—a lightning quick excursion, arriving back in time for sked—that I didn’t even bother to let my lookout neighbour, Dan, know of my whereabouts.

I jogged a few kilometres down the grassy road that led through old growth spruce and turned around to head back home, when a few hundred metres ahead on the road, I saw him: a hulking black bear parked like a bus, head down, hoovering clover. I took note of the bear’s large muscled shoulder and wide skull. Likely a male, I thought.

I knew I only had fifteen, twenty minutes, at best, to make it back to the cabin for my radio check-in, So I had a choice to make: try to hurry, or “gently encourage” the bear off the road so I could continue on my way, Or wait him out at a safe distance and risk missing the mandatory call.

I could just imagine the conversation I’d have with the Duty Officer. It’s seriously frowned upon missing a radio call at the lookout. Your job is essentially about listening and responding to the radio 24/7. A “nothing heard” response would send a ripple of concern through the forest. My colleagues would worry where is she? what went wrong? They might even dispatch a helicopter to look for me. I was so appalled by the idea of having to admit that I’d made so many rookie mistakes in my 7th year as a lookout that I did, what exactly?

I made another dumb mistake: I decided to pressure the big male off the road.

I slowly stepped forward towards the bear, my dogs glued to my side. We moved like a single organism. I gave him a courteous heads up, “Oh, hey Bear! We just need to get by…”

We’d done this before when necessary (albeit with smaller, less dominant bears) and it had always worked. The youngest of the bears would typically dash away into the bush, their fleshy rumps bouncing.

But the big male didn’t budge, didn’t even bother to lift his head. Bear do this sometimes, you know, pretend they don’t see, or notice you there, feigning indifference. Biologists call this “ignoring behaviour”. I knew the bear knew we were there and, at 200 metres away, he showed it, swivelling on his rump, strolling towards us, head down, ears pressed to his skull.

Previously, I’d been bluff charged not once, but twice, but there was something far more unsettling in the slow, intentional way he approached us. I got the distinct feeling that this encounter was not a bluff. This was the bear reminding me of my bad manners, my disrespect of the law of bears. This was the bear teaching me a valuable lesson.

I saw the flash of the white O blaze on the bear’s barrel chest. It was Oscar, I realized, the dominant male in the forest. I remembered the way I’d seen Oscar bully other males for territory and breeding rights. There was a reason he scratched his oily back and marked his claws into every power pole lining the road, as though carving the words MINE.

Oscar was Boss. Oscar owned the place. I was so frightened, I froze on the spot. I just stood there, dumbly, as he strode towards us, paws flicking the dirt.

Oscar in Spring 2020.

The dogs didn’t bark, but stood alert on my side. The canister of bear spray felt feeble in my hand (despite the fact that I knew, statistically, bear spray is one of the most effective deterrents in close-range encounters). I didn’t want to have to detonate it. It took several long seconds for my brain to send the message to my feet: RETREAT.

I stepped backwards slowly, speaking to Oscar as though reassuring a kindergartener.

“Okay, my bad, my bad,” I crooned to the gargantuan bear. “Sorry to have bothered you, big guy.”

This spatial show of respect worked worked almost immediately. Oscar turned around and resumed grazing, as though nothing had happened and I accepted the inevitable. I’d miss my radio check-in and have to later apologize to my colleagues and supervisors. I might take some heat, but it wasn’t worth a negative encounter.

The bear taught me a valuable lesson that day: SLOW DOWN. Bears AREN’T in a great rush the same way we are as people.

Bears move according to their own agendas. If you follow their tracks, you learn how they rarely walk straight lines. They frequently double back. They’ll investigate anything new. They’re curious, opportunistic, and tangential in their movements.

Big Mama. Late summer 2021.

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on the value of this lesson, but in the context of WRITING A BOOK. we live in a world of urgent storytelling. it’s so easy to feel that pressure to hurry a project even knowing that good books take time—sometimes even decades—to get just right.

I know this, but even still, the process can be frustrating, at times. You pour yourself into an edit, or narrative restructure, and surface from the experience wanting to believe it’s done, while deep down, knowing, it’s not yet done. It would be so easy to say fuck it and move on to the next project. It’s so easy to get caught up in the curse of comparison, “the thief of joy”, as Roosevelt said. You see other writers publishing books and going to literary events and giving interviews and it’s so hard not to feel like: will I ever get there?

That’s how I was feeling a few months ago with my memoir, Black Bear—this gnawing, melodramatic feeling that maybe I’d never finish the book. Maybe I’d be writing and rewriting and editing this project for the rest of my life. Five years is fairly standard when it comes to the book writing/publishing timeline, but knowing this doesn’t cancel out feelings of self-doubt. Maybe I’ll never get it right.

Black Bear began in 2019 when I started my MFA at the University of British Columbia. It began with a poem called An apology to Ursus americanus, which tried to capture the contradiction between saying we love bears and the reality of living closely with them, which I swiftly learned, in my first year living in the bear corridor, is not always easy, or harmonious. The poem read like one of Pablo Neruda’s odes.

I want you to be more myth / than matter of fact / a drawing on a cave wall / a handful of stars that draw the gaze north / a tourist attraction along a fenced highway / in a national park / but not here, now, with hardly an exhale between us.

This poetic apology grew into a thesis proposal to write a non-fiction book about human-bear coexistence. The proposal involved travelling to places where people lived closely with bears—a rehabilitation centre in northern B.C., the Great Bear Rainforest, Churchill, Manitoba, and so on. But then, well, the pandemic broke out and the story was forced to change course. The narrative became a study of my own story in relation to the black bears that lived around my fire tower. The first draft was, I’ll admit it, fairly unreadable (and yet, my closest friends still generously read it).

The earliest drafts of Black Bear were a nebulous gathering of ideas that wanted to relate to one another, but couldn’t quite connect on the page in the way I intended them to. That, no doubt, irked me. But then, as I moved through the seasons at the fire tower, 2020, 2021, and 2022, my relationship with the bears evolved, deepening, and the words about their behaviours, their individual traits, and their patterns found their way onto the page. My ideas about bears and the complexity of human-wildlife coexistence and conservation broadened.

Osa, a bear whom I watched over four seasons, in Fall 2020.

The process of writing Black Bear has been the most challenging literary project that I’ve worked on, to date. By comparison, Lookout felt a walk in the park. Like I knew what I wanted to say as soon as I sat down to write.

BUT Writing Black Bear has been, to paraphrase Annie Dillard, like wrestling—not an alligator, as she SUGGESTED—a bear.

I’ve been forced to accept a different pace with this project and that books inevitably change, as we change, over time. The writing of this book has contained so much upheaval, which has, no doubt, influenced every iteration. The COVID-19 pandemic, the death of my brother, leaving the fire tower, a winter in the Great Bear Rainforest, relocating to Whitehorse, a new relationship. I’ve now worked on the manuscript while living at the fire tower, in Peace River, Dawson Creek, Atlin, the Nekite Estuary, Carcross, and now, Whitehorse. Geography, world events, personal events. These factors (and many more) often shape the texture and trajectory of the stories that authors set out to write.

In writing Black Bear, the narrative has moved at the pace of a bear: often doubling back, traveling tangentially, exploring new pathways, while incrementally EXPANDING different ideas about coexistence and conservation.

The rewards of not rushing creative projects are many.

There is still work to do yet, another round of edits before the book goes to copyedit, but we are getting closer now. I am fortunate to have had an enormous amount of support from friends, fellow writers, and talented editors.

With a little luck (and a lot of work) Black Bear will come out Fall 2025 with Knopf Canada.

It’s an understatement to say that I really can’t wait to share the book with you all.

Anyway, as it turned out, I didn’t have to wait long for the bear on that day in 2022. I gave Oscar the space he deserved and, after a few short minutes, he returned the gesture. The bear ambled off into the bush and I was able to make a mad dash for home with seconds to spare.

(I never forgot my hand-held radio again, for the record).

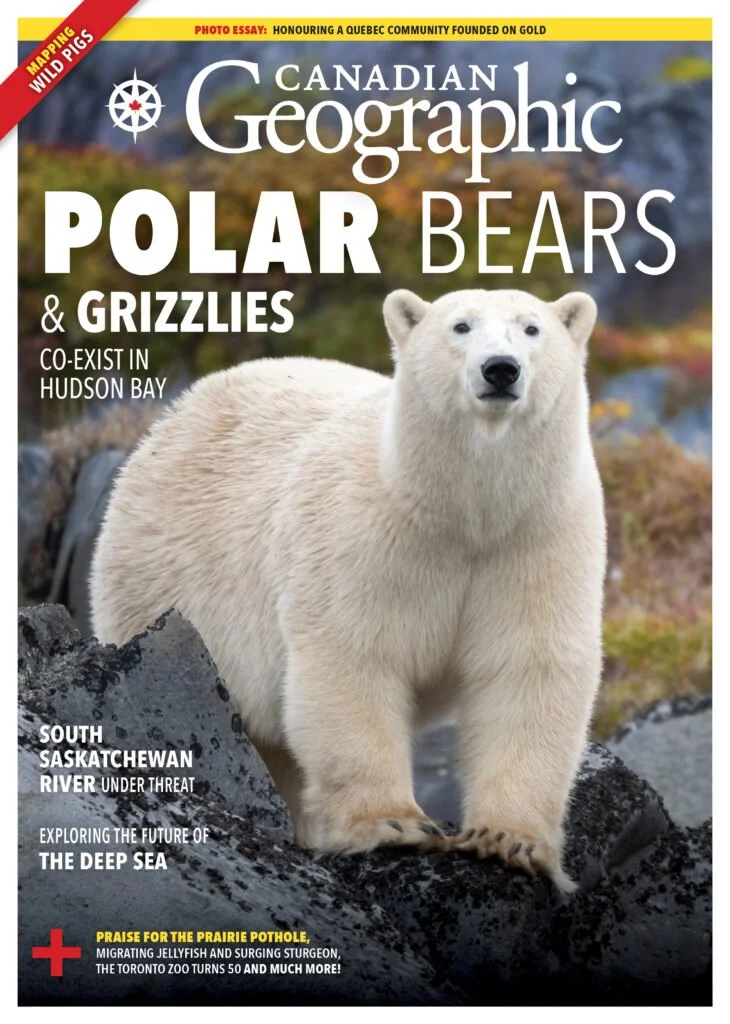

In other bear news, I’m pleased to share that my story about the rise of grizzly bears in polar bear country in the Lower Hudson Bay was featured on the July/August cover of Canadian Geographic.

Last year, I traveled to Churchill, Manitoba, and worked closely with photographer, Drew Hamilton, to report on this story that focuses on research led by Dr. Douglas Clark at the University of Saskatchewan.

I’m grateful to many for their support of this story, including the Northern Studies and Research Centre, Travel Manitoba, and the editorial team at Canadian Geographic (especially my editor, Michela Rosano).

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider “buying me a coffee” to help support my work as a writer.