Haunted by the Grey Ghosts

FEATURE ARTICLE FOR THE NARWHAL ON CARIBOU AND WILDFIRE—AND A NEW BOOK ON THE HORIZON

Over the past few months, I’ve had caribou on my mind. I’ve always been haunted by stories of caribou, a species that my father, a biologist, calls the “grey ghosts” of the boreal forest. But lately, I’ve been thinking of caribou in the context of the escalating wildfire crisis.

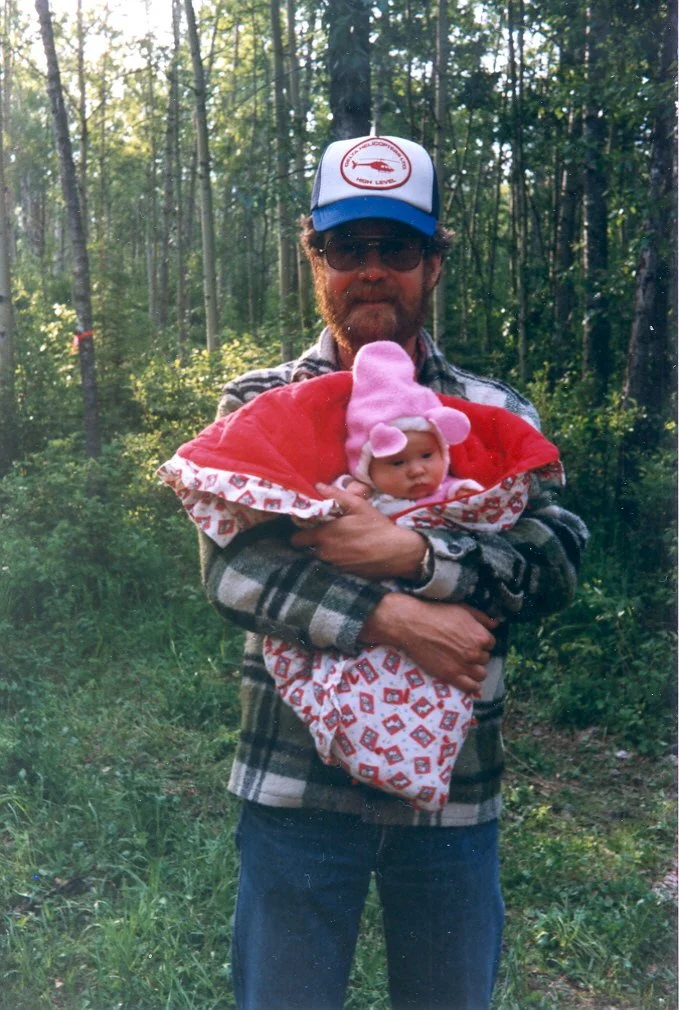

I grew up with woodland caribou, or at the very least, the idea of them. From 1989 to 2017, my father brought home tales of his flights over forests in northwestern Alberta, counting dwindling caribou herds. The late 90s and early 2000s represented a boom in oil and gas exploration in northern Alberta. Companies, in their quest for resources, made scissor work of the landscape. That’s never boded well for caribou—both woodland and barren-ground species—who need uninterrupted habitat for their survival.

Some herds have disappeared entirely. Others are barely hanging on. The caribou around my hometown of Peace River could be a few decades, maybe less, away from extirpation.

After the 2023 wildfire season, which saw unprecedented numbers of area burnt—over four percent of Alberta’s forests—I couldn’t stop wondering: how much is too much?

Last fall, I’d interviewed Dr. Mike Flannigan for a feature in Alberta Views and his words rung in my ears: “If this was an average year in the past, there’d be no forest left because forest cannot survive a fire cycle of twenty-five years.”

Caribou need forests that are at least forty years old. They rely on mature boreal ecosystems, gleaning proteins from delicate lichens that grow from black spruce boughs, or in boggy swamps. Caribou are so hardwired to lichen they can scent it through four feet of snow.

What do these increasingly frequent, volatile wildfire seasons mean for a species that favours old growth? How have caribou naturally evolved with wildfire over millennia? How are they responding to the situation today, despite the many other human-caused pressures they’re facing?

Map by Ryan Cheng at CPAWS Northern Alberta chapter showing the disturbances by wildfire from 1984-2023 with human disturbances in caribou ranges in northwestern Alberta.

Over the last few months, I’ve spent hours on the phone with my father and other experts, including Dr. Laura Finnegan, lead caribou researcher at fRI Research in Hinton, Alberta, and Stephanie Leonard, who runs Caribou Patrol with the Aseniwuche Winewak Nation in the Grande Cache region.

People’s fear for the future of woodland caribou in Alberta is palpable.

“There’s so little good caribou habitat left there’s a worry that, if it burns, where are the caribou going to go? Is that going to be the end?” Leonard told me.

Last week, I published an in-depth essay about the impacts of wildfire on caribou populations with The Narwhal. I’m grateful to editor, Sharon Riley, who invited me to write through a personal lens. For me, it always comes back to my father’s work as a biologist. For three decades, he documented the steady declines of woodland caribou in northwestern Alberta. Like caribou, my father’s words about habitat and species loss have always haunted me. I will forever migrate back to the lessons he imparted with me.

Read the full-length essay Grey Ghosts in the Smoke.

An image captured by a trail shows a caribou from the Bistcho herd walking through a forest that burned eight years ago. “This is the only caribou we found at this site over three years,” Ryan Cheng with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society says, noting woodland caribou avoid burnt areas. Photo: Supplied by the northern Alberta chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society and Dene Tha’ First Nation.

More writerly news to share with you all—I have a new book on the horizon!

Recently, I was honoured to receive the Yukon Advanced Artist Award, which is enabling me to start researching and writing my first novel about a biologist based in northern Alberta who finds herself embroiled in environmental conflict surrounding the conservation of woodland caribou habitat.

The concept for my novel began in 2020 as a short story assignment for my MFA program. Only a few years earlier, I’d read in the news about a caribou that was shot and dumped on a farmer’s field in northern Alberta. I’d always wondered: who was behind it? And was the carcass of the threatened species sending a political message to government and conservation organizations?

Caribou have become increasingly politicized in rural communities in Canada’s north. To ecologists, they’re an indicator species of environmental health. To many Indigenous communities, they’re a lifeline; they’re woven into cultural identity. To others, they’re seen as an impediment to resource extraction; that protecting caribou could result in the loss of jobs—and the viability of rural communities.

After nearly a decade of working in literary journalism and creative non-fiction, I’m eager to challenge myself to work in a new genre and approach this story through a fictional lens. I’m excited to build characters—with all of their messy contradictions—from the ground up.

I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t daunted, or a bit intimidated to attempt a novel, but I know one thing to be true: that writing a book, whether it’s non-fiction, fiction, or poetry, requires a haunting of sorts. The author has to be possessed by their subject in a way that allows them to continue caring long beyond a few days, or even months, but years.

That the story of woodland caribou—an indicator of the health of the boreal forest—has continued to follow me around like a ghost is a good sign that it wants to become a book. Wish me luck as I wade into the unknown of writing a novel.

Finally, I’m excited to announce that I’ll be launching a monthly Field Notes newsletter in September.

For meandering essays about conservation, land, and stories that inspire me, along with updates on my book and documentary projects, please sign-up to receive the newsletter by email. I’ll also include my recommendations on books and articles to read, podcasts to check out, and films to watch.

As always, I’m grateful for your care and support.

Thank you for reading!

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider “buying me a coffee” to help support my work as a writer.